Basic Info

Name: Charles Mattox

Country of Origin: US

Description

Although Mattox’s history is not widely noted, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., has taken special care to preserve a large repository of his work. The University of New Mexico is fortunate to own two of Mattox’s kinetic sculptures. Mattox’s obituary notice in SFGate states that “He joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley, but was induced to move to Los Angeles, where he became associated with the Ferus Gallery.” There is, however, no evidence – as gleaned from exhibition lists and interviews with Ferus Gallery artists – that Mattox ever exhibited there.

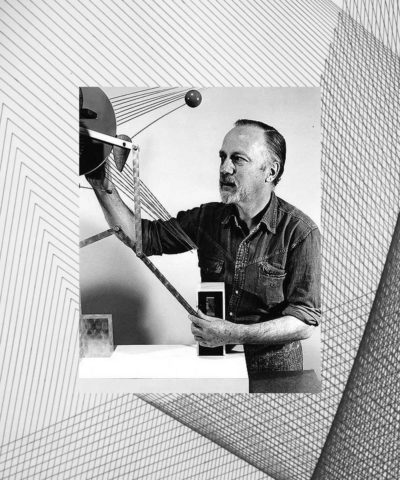

Charles Mattox’s life was doubly bifurcated, at least. Mattox was a muralist, an educator, a sculptor, and a set designer. He was active in Kansas, New York, and in Taos, Santa Fe, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, as well as in Hollywood and San Francisco, California. He grew up in Bronson, Kansas, a small town about a hundred miles south of Kansas City. His mother was a painter, and Mattox started painting when he was about ten years old. He spent his undergraduate years at nearby Bethany College, where – beginning at around age nineteen – he studied with Burr Sandzen (Birger Sandzén). After completing his undergraduate studies Mattox studied at the Kansas City Art Institute for a year and a half, and then made a commitment to himself to get admitted to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. As Mattox noted, “It was during the Depression, I couldn’t get a job and couldn’t make it there, so I came back and worked in Kansas City for a while to get some money. Then I went to New York. I worked for about six months for an interior decorator and during that period met a lot of the artists who had come on to New York from Kansas, that I had known at the Institute.” (Interview with Charles Mattox on April 9, 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

In the early 1930s Mattox studied and worked – through the Works Progress Administration – with Fernand Léger, Jean Charlot, Stuart Davis, and David Smith and Arshile Gorky, with whom Mattox apprenticed as a painting student. Mattox was primarily involved with mural projects at various schools and institutions. “Well at that time, the work I did was for myself.” stated Mattox. “The work I did for the project was primarily supervisory at that period. And I painted a lot. … I was very interested in what Gorky was doing and studied with him. He had a small group who worked in his studio. And I met all these artists and was very much stimulated and got involved in projects at that time. Léger had come to New York … [He] was very interested in what the project was doing. He was a very good friend of [Burgoyne] Diller’s. A group of us got together. Diller organized a group that designed things for a mural, but as an independent job, and we worked on this when we weren’t working on our project … the French Line steamship company. It was an interesting idea we were going to do … the inside of a long pier, which was corrugated sheet metal, and we were going to do large “Léger-like” forms of undersea life in baked enamel bolted to the surface to make a very gay, colorful carnival effect inside the steamship loading pier. However, the French Line never came through with the money, and the project was never completed. It was a very interesting period for me because I came in contact with these people who later had a great deal of influence on my own work. There was a photographer on the project, Stuart Davis’s brother, Wyatt, who became a very close friend of mine, and I spent a lot of time with him. He worked as a photographer on the project. He was also a very good friend of Gorky’s.

I remember Jackson Pollock really well. He was on the project at that time. Ben Shahn was also on the project, as well as Lou Blond, who I first met when they were working with Diego Rivera on some murals in New York. Shahn left the project to take a Farm Resettlement Administration job as a photographer.” (Excerpts from an interview with Charles Mattox on April 9, 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

In the early 1930s, Mattox was hired by Diego Rivera to grind pigment for Rivera’s murals. Unfortunately, Mattox joined the Rivera team the same day the Mexican painter was fired by Nelson Rockefeller from the Rockefeller Center building project over the revolutionary political content of the mural. In 1935, weary of the WPA bureaucracy and eager to do his own work, Mattox left New York. His first stop (he was married at the time) was a teaching job in Arkansas. Mattox only stayed in Arkansas for six months. During this period Mattox’s friend Wyatt Davis came through Arkansas on his way to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and convinced Mattox and his wife to move to New Mexico. So, in 1936 Mattox and his wife hitchhiked to Santa Fe. According to Harwood Museum of Art Director Emeritus Robert Ellis, “Mattox and his wife were extremely poor, basically living a ‘hobo’ lifestyle.” In Santa Fe, Mattox did work with the American Index of Design, making color plates of icons and early-American art objects. Many of these watercolors were used for book illustrations. During this period Mattox did not associate much with the other WPA artists, finding friendships instead with John Sloan and Will Shuster. Mattox recalls his time in Santa Fe: “There were a lot of writers and some musicians that I got acquainted with there and had later connections with. We worked at home and didn’t come in contact with anybody else during the period of my stay. It was a home project. I was living on Canyon Road at that time, and I met a number of writers: Harvey Bright, Kenneth Patchen. Kenneth was in Santa Fe at that time and I got to know him very well. As a matter of fact, he and I started working on some books. I was doing some illustrating for him, and then we left Santa Fe and went to Los Angeles on a basis of a contract we had gotten to do a comic strip together. My wife and I went to Los Angeles with Kenneth Patchen and his wife Miriam, and we lived together in Los Angeles — or rather in Hollywood — when we got there, for about six months. The outfit that bought the comic strip folded, and we never got anything except our initial payment out of it, which had enabled us to get to Los Angeles.” (Interview with Charles Mattox on April 9, 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

That was in 1937. Mattox and Patchen continued to work, but sold very little. Patchen had a Guggenheim Fellowship, but Mattox had no income. After becoming completely destitute, he took a job in a Los Angeles sign shop. It took every ounce of energy to survive in L.A. In a recent interview, Mattox’s daughter, Ginger Grab, stated, “My dad told me they moved 22 times in Los Angeles; he may have been exaggerating — he was quite a storyteller.” Six months later, Mattox was hired to work on an easel project — “they had sort of run out of wall,” he says — inside a gallery on Seventh Street. Like the murals, the easels were a Works Progress Administration project under the direction of Stanton Macdonald-Wright, the co-founder of Synchronism. It was here that Mattox came into contact with a number of significant painters — Ben Burlin, Herman Cherry, Denning Withers — and got involved helping photographer Leroy Robbins, who was heading the filming of the easel project. It was with Robbins that Mattox became more involved in film, having already created some experimental films of his own.

In the beginning there were just two of them; Leroy Robbins was the cameraman. They shot 16 mm color film, with the sound track laid down after shooting. The films were shown at schools and to various organizations who were interested in what was going on with the easel project. Mattox stated, “The artists found [Macdonald-Wright] very difficult and didn’t like him particularly. I think that was generally true. I found him difficult. Another thing was that he was politically very reactionary. He was a Republican and he didn’t really believe in the project. He thought the whole idea was not a good one. There was an attitude on the project that was pretty much his doing, which the artists resented. There was always a great struggle on the Los Angeles project between the Artists Union, which was not as strong as in New York, where it was a very strong factor in the project and had a lot of power; it was very weak in Southern California. They did have some members and they tried to do things around project policy but were fought always by Wright who was very anti-union, and of course Los Angeles was an anti-union town in those days and it made quite a difference.” (Interview with Charles Mattox on April 9, 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

The Hollywood studio unions were very strong at that time but did not lend any support for alternative art projects, although some of the stars were quite interested and would come by the gallery to see what the artists were doing. The studio unions were very conservative unions at that time; some of them run by racketeers. ” . . . during that period Brown and Bioff were in control of the Hollywood unions, and later they were thrown out – Bioff was sent to jail and Brown was thrown out. But Zanuck in later testimony said that during those years, right during that period, Bioff and Brown had been paid a million dollars in kickbacks, and this came out in a Senate investigation of the unions later.” (Interview with Charles Mattox on April 9, 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.)

Mattox continued to work in the motion picture industry until 1950, when he and his wife moved to San Francisco, where he evidently remarried and had a child. Mattox became a well-known drawing teacher at the California School of Fine Art, later the San Francisco Art Institute.

Charles Mattox was one of the most important artists traversing the east and west coasts during the nation’s most vital artistic times. In Taos, we have an orderly way of dissecting eras. Mattox is one artist who cross-pollinates between east and west. In his lifetime he was a player in the New York WPA, working with the most important artists of the time. He paid his wearisome dues in the Midwest and finally became part of a major movement on the West Coast. Not only was Mattox working and teaching there, he was also experimenting with some of art’s most unusual tools of the time. Abstract Expressionism had swept the art world, but his leftist views led Mr. Mattox to reject the new style as an abdication of social involvement. He began dealing with the human relation to technology in kinetic sculptures, which involved motion and sound.

He eventually settled in Albuquerque, teaching at the University of New Mexico. There, he programmed computer drawings and lectured on the relationship of art and science. He retired in 1976.